24 Jan 1962: Civil Rights and Black Power at CBTA

By Michael Becker

James Farmer (far left), director of Congress on Racial Equality, addresses the audience at the Cornell debate, as moderator Rev. Paul L. Jacquith, director of CURW, and Malcolm X (far right) of the Nation of Islam look on. Used with permission of the Cornell Sun. By 1962 Sun staff photographer Robert F. Levy.

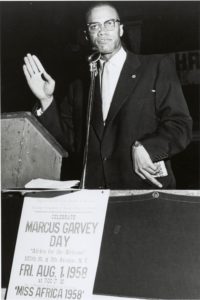

In May 1962, Cornell hosted a remarkable debate between two leading intellectuals and activists around Black freedom: Malcolm X, then representing Elijah Muhammed’s Nation of Islam, and James Farmer, president of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. At the time of their debate, Farmer’s name was on the nation’s lips. He had achieved nationwide celebrity as the originator and spokesperson of the Freedom Rides, in which integrated groups of Black and white passengers rode interstate buses in mixed accomodations into southern states. The buses were invariably met with protests and violence, sparking the Justice Department to take reluctant action in support of integrated interstate transportation. Malcolm X was still seen as a chief deputy of Elijah Muhammed and noted for his advocacy of racial separatism, his strong criticism of the emphasis of the civil rights movement on Black participation in the formal political process, and a firm advocate of Black self-defense “by any means necessary.” He had earned a reputation as a powerful orator and had already garnered international interest, meeting with leaders from Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea, and Fidel Castro.

The sponsoring campus organizations – Cornell United Religious Work, Dialogue Magazine, and the Cornell Committee Against Segregation – glossed the debate as a contrast between separation (represented by X) and integration (represented by Farmer). Campus interest was high; there were more people interested in attending the event than available tickets, and sponsoring organizations were unable to secure a larger venue at short notice. According to Cornell Sun reports, Farmer described Americans as suffering from a split personality, believing in freedom, democracy, and equality, but failing to practice it. He claimed that Black

Malcolm X addresses a 1958 Garvey Day gathering in NYC. Courtesy: New York Public Library, Schomburg Collection

Americans were solving their own problem, through organizing Freedom Rides and sit-ins in a quest for integration. X, to the contrary, decried white Americans as hypocrites for their stated belief in equality and freedom, and said that Black Muslims were not interested in integrating with people who did not want them. The Cornell Sun’s writers were clearly more sympathetic to Farmer’s argument, but expressed surprise at X’s eloquence and poise. Some writers clearly viewed X and his message suspiciously; one unnamed columnist charged that X had softened his message for a predominantly white college audience and was fomenting rage in working class Black communities that would harm efforts at racial harmony. Reporting by the Sun underscores that many Cornellians placed greater emphasis on the tone and ‘civility’ of civil rights discourse than the denied freedoms and civil liberties of African Americans.

Following the debate, both men attended a reception at Telluride House. Brian Kennedy SP60 CB61 TA63, then a CBTA freshman, describes the scene as follows: “After the debate, both came down to Telluride House for what seemed a rather well-attended reception. As you turned left from CBTA’s front door into the living room, immediately on the right was the refreshments table. Just beyond it, along the wall, was a couch. Seated alone at the center of the couch, with a crowded circle of us around him, listening and questioning, was the spellbinding borderline-strident ascetic Malcolm X, commanding the room. One young black woman…, politely fast on her feet, was strikingly articulate in contesting his domineering separatist vision… Standing directly in front of Malcolm X, maybe 15 feet away, with a softly-speaking smaller circle standing around him, was James Farmer, nursing a tumbler of whisky.” It’s unclear if either man stayed at Telluride House during their visit to Cornell, although neither have signed the guest book. It is worth noting that their visit occurred during prominent conservative intellectual Allan Bloom’s residence and while future World Bank President and US Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz SP60 CB61 TA62 was a house member.

In the next semester, the House was also paid a visit by the famous novelist, essayist and cultural critic James Baldwin. At this point, Baldwin had published two novels: Go Tell it on the Mountain, a coming-of-age story of Black teenager Charles Grimes and his evolving relationship to the Pentecostal Church, and Giovanni’s Room, noteworthy for bringing a complex representation of homosexuality and bisexuality to a broader reading public. Two of Baldwin’s both notable essay collections, Notes of a Native Son, and Nobody Knows My Names, had also been released. We know of his visit from a signature in our guest book and a rather bland notice from the 1963 CBTA President’s report, which describes him only as a “Negro writer.” Yet, the Cornell Sun contains no coverage of his visit, as it would of many lectures and public presentations on campus, although certainly not all. Initial inquiries to a few alums from this period have not – as of yet – yielded any specific memories of his visit. We would love to know more, if any blog readers were around CBTA at the time.

Theo Foster

Posted at 11:48h, 03 FebruaryGreat archival work Michael!

Michael Chanowitz

Posted at 10:50h, 06 FebruaryI was a sophomore living at CBTA at the time. Oddly I do not remember the debate, the reception, or anything about James Farmer’s presence. What I do remember is that Malcom did spend the night at the House and that a small group of us kept him up talking late into the night. The discussion was lively and Malcom hewed close to the “white devil” rhetorical line that he followed at the time, but I vividly recall that under the rhetoric I had a strong sense that he was empathizing and even identifying with us. I had the feeling at the time that he was sensing a kinship with us, a bunch of smart, intellectual kids, realizing that under other circumstances he might naturally have been one of us. So I was not surprised when he later left the Back Muslims, turning away from separatism and toward a universal approach to human rights.

It’s also odd that I don’t recall Baldwin’s visit although I’d read all his published work. His writings had a lot to do with my decision to spend a year (65-66) in Alabama teaching at Tuskegee Institute and working with SNCC. I met Stokely Carmichael that year in Alabama and got to know him a little. Later, when I returned to Cornell for graduate school and Stokely had become the leader of SNCC, I hosted him for a night at CBTA when he came to give a talk on campus. A funny story: when he was leaving I drove him to the airport and began to carry his suitcase into the terminal. He quickly took it from me, saying he didn’t want to chance a newspaper photo of him (six feet tall) accompanied by a little white guy (five-six) carrying his rather large suitcase. Stokely, who is best known for initiating the black power movement, was another strong, militant black leader of great intelligence and humanity. During my year in Alabama I was privileged to observe his genius as an organizer of the disenfranchised black population in viciously racist Lowndes County, perhaps his finest work.

Matthew T Trail

Posted at 11:59h, 06 JuneJust reading this now. Thank you so much for sharing these recollections, Michael!