20 Jan ACLU Attorney Miriam Aukerman: “Telluride teaches you to see the impact of the decisions you make”

by Maia Dedrick

![]()

Miriam Aukerman SP86 CB87 TA88 is a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Michigan, and manages the ACLU’s West Michigan Regional Office. Miriam graduated summa cum laude from both Cornell University and the New York University Law School, where she received numerous academic and public interest awards. She is a 2012 recipient of the Criminal Defense Attorneys of Michigan’s Justice for All Award. She spoke with me over the holiday break.

Just to frame our conversation, I’d like to learn what you’re doing and maybe how Telluride inspired you to do that. In particular, could you talk about your path to the ACLU in Michigan?

I took a circuitous path to the ACLU. While at Telluride [CBTA], I took a semester to live in what was then Leningrad and was really taken with that. I studied International Relations as a Keasbey Scholar at Oxford, then came back to the United States and worked at the Ford Foundation for a couple of years doing grant-making work around human rights. Then I lived in Moscow for awhile and was planning to take a permanent position, when my father became very ill. I decided I wanted to be back in the US. I thought about what I could do that would contribute to my future in international human rights work and decided I should go to law school for the period of time I wanted to be back in the US.

I’m married to another Tellurider [Chuck Pazdernik SP85 CB86 TA87] whom I met when I visited CBTA even before joining the Branch. Chuck is a Classicist, and he got a job at Grand Valley [State University] in western Michigan. We had a long distance relationship for awhile, and at that point we decided we wanted to be in the same place. When we moved to western Michigan, I decided I wasn’t going to pursue the international human rights work that I’d gone to law school to do. I clerked for a year and then I took a job at a legal services office doing poverty law, which was not at all what I had thought I would do when I went to law school. I really loved the work, and representing clients. The law suits me very well.

I spent about 10 years as a legal aid lawyer, and after a couple of years I got a fellowship that allowed me to concentrate on the intersection of civil and criminal law, so focusing on the impact that criminal convictions have on people’s housing and employment and on other aspects of their lives. Michigan is a relatively small public interest legal community, so there’s tremendous need and relatively few lawyers who are dedicated to doing this kind of work. I also did a bunch of volunteer work at that time for the ACLU on first amendment issues and civil rights issues. When the ACLU decided to open a west Michigan office in 2010, I was hired as the original and only staff attorney for that office. The work that I do now is largely poverty work, immigration work, and criminal justice work.

The law is a tremendous profession because in public interest legal work you have the opportunity to use your writing skills and intellectual abilities to transform the world in very concrete ways, but at a systemic level. You change people’s lives, you change systems, and you change the way laws get written or enforced by essentially having the better argument. That’s something I learned a lot about at Telluride.

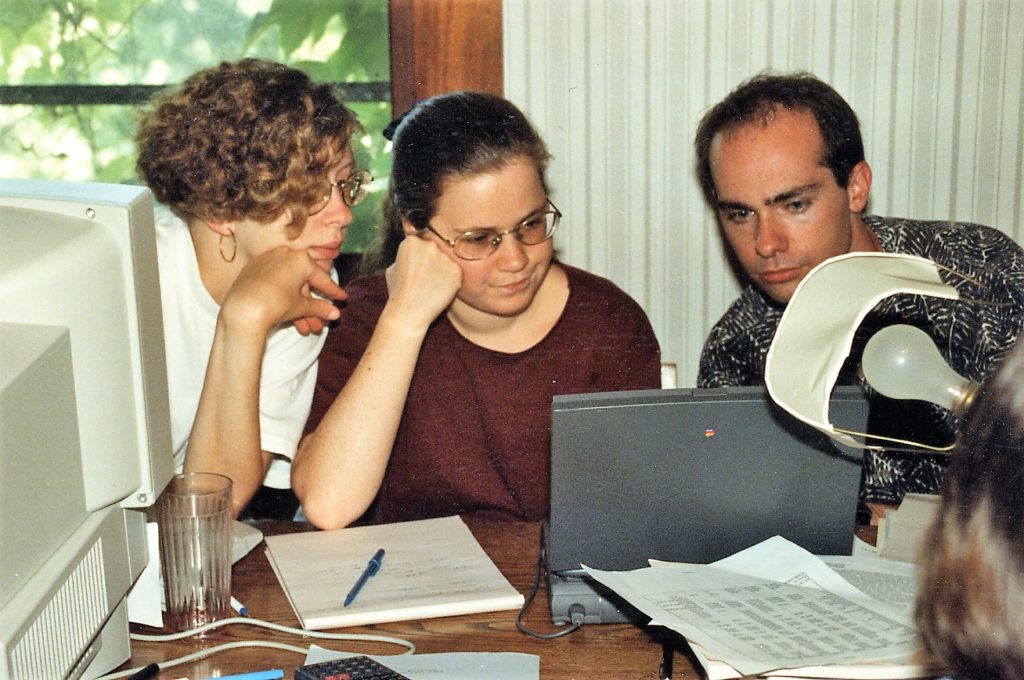

Miriam Aukerman (center) at the 1996 Convention, getting the numbers to add up. Also pictured: Jessica Cattelino SP91 CB92 TA93 (left) and Tom Hawks SP85 CB86 TA87.

Telluride was really one of the most transformative experiences in my education. I was a long-time Association member and before that a branchmember. I think what you learn is to work with other people, and everything I do now is in teams. We are all so much smarter in groups. Listening to other people and figuring out how to make decisions as a group is certainly one of the seminal things I learned from Telluride. I also think that Telluride taught me to reflect on myself and to try to figure out how to improve things, both in terms of how systems work and the mistakes I make. We learned so much more from the summer program that didn’t go well than the one that went swimmingly by reflecting on what didn’t work. The other thing I do a lot of in my career now is work with volunteers. At the ACLU we actually have a pretty small legal staff, and we punch far above our weight because we harness the power of like-minded lawyers and non-lawyers who want to engage in legal activism and to protect people’s rights. To do that you need to figure out how to get volunteers to do things and to do them on time. That’s certainly a challenge that anybody who has been at all involved in Telluride would know about.

I recently saw a case you are working on come up on Facebook. Could you describe that case?

The main case is called Hamama v. Adducci. The Trump administration cut a deal with Iraq as part of the travel ban, in which Iraq agreed to take back some uncertain number of individuals who had been ordered removed. Iraq has for decades not agreed to accept individuals back. Many people came to the United States as refugees because of political turmoil and sectarian violence and persecution of religious and ethnic minorities (really genocidal persecution) in Iraq. Many of them might have been ordered removed years or decades ago, and since they couldn’t be, they went on to live very successful and productive lives. They raised families and built businesses and watched their grandchildren grow up. Suddenly, without warning, in June of this past year, the administration rounded up hundreds of Iraqis. There’s over 1,400 Iraqis in the US who have been ordered removed over the past several decades. By the end they rounded up about 300 now in detention. We ran into court to stop the deportations, because those individuals face very significant likelihood of persecution, torture, or death if they’re sent back to Iraq. Just about any time you rip a family apart it’s traumatic, but here the stakes could not be higher. These are life and death decisions that are being made.

We went into court, and we were able to stop the deportations. That aspect of the case is now on appeal, and we were just in court last week again trying to argue for their release. These are people who have now been in detention for six months for absolutely no reason. They’re all people who had been living in the community for many years, decades, and there’s absolutely no reason they should be in jail while they’re waiting for their immigration cases to work their way through the immigration court.

What does your day look like day-to-day managing all these different projects?

Every day is different, which is one of the things I like about being a lawyer. Some days I’m in court, more often I’m not–I’m writing briefs, doing legal research, talking to clients, and talking to cooperating attorneys. I spend a lot of time working with other people and writing. I spend a lot of time thinking about how you frame arguments, and how you convince people to see the world in the way you see it. We live in an incredibly unjust world. When you talk to clients and you go to court and you see people’s kids sitting there waiting and telling you that all they want for Christmas is their dad to come home–you need to be able to convey that emotion to people who make decisions, like judges and policymakers. Law is really a profession of translation, because what you’re doing is you take people’s real lives and you translate those into this abstract legal language that has its own bizarre grammar. You try to get results for people and turn their lives and stories into something that judges can understand and that fits the rubrics of constitutional values and a statutory framework. When something new comes in, your first reaction is “this is so unjust, this must be unconstitutional.” Then you take that story and that feeling of incredible indignation at what the government is doing to people, and you translate that into a legal argument that you hope becomes the basis for an end to that injustice.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

One other thing I would just say is that when I moved to Michigan, we got really involved in Michigan Branch when it was just getting started. I’m not involved actively in the Association anymore, but it is tremendously gratifying to see, as an older person, the fruits of so much labor that went in. I drive by the house now and remember all the blood, sweat, and tears that went into making that. I was one of many, many, many people who was involved. Telluride teaches you to see the impact of the decisions you make. That’s a thing you can take with you for the rest of your life. When I drive past the house, I think, here’s a difference you can make in the world. There are now I don’t know how many people who have gone through the Michigan Branch since we set it up, so you think, wow, lots of people’s lives have been fundamentally affected by the work that people put in to make that Branch a reality. We really do, through Telluride, and through the rest of our lives, have the ability to actually impact the world, make it a better place, give people opportunity, and we need to continue to do that. Telluride is a tremendous opportunity to see that in action, to see how much people working together can accomplish.

Gil Sander Joseph

Posted at 14:16h, 22 JanuaryVery inspiring! I hope that many people will recognize it is up to us to make the first step toward actual change.